Back Pain, Breath and Core Stability

by Madeline Stewart Oct. 31st, 2018

Do you experience low back pain and/or tightness in your shoulders and neck? These are widespread complaints amongst musicians, and they are often attributed to long practice/performance hours in uncomfortable positions and chairs. However, there is a high possibility it is a result of the way you are breathing. Seems crazy right? If practice makes perfect, and we breathe over 23,000 times a day, how can we possibly do it incorrectly? Well, there are many reasons we can develop improper breathing habits; job-related movement patterns, stress, old injuries, scar tissue, PTSD... but arguably the most common cause/symptom is improper posture. Improper posture can be the cause of, or the result of, incorrect breathing patterns. In my experience, it is much more effective to shift the pattern of breathing (and posture will follow) than to address posture (and hope breath repatterning with follow). For this reason, I always start with the breath with any client experiencing back pain. But, before we get into the how let me tell you a little bit about the what and the why.

Back pain is the leading cause of disability in the world, and it is estimated that 80% of the population will experience back pain at some point in their lives! [1] There are many different conditions and contributing factors that lead to back pain, acute or chronic. The information in this article is not presented as a cure for all back pain, but rather a look at one common contributing factor and a simple and effective approach to back pain resolution.

Odds are, if you have or are experiencing back pain, you have been told that your pain is due to a “weak core.” This isn’t completely wrong, but unfortunately, the definition of what our core is, and the most common exercises marketed for a “strong core” are missing a huge part of the overall picture, and therefore are rarely effective. What is essential is true core stability that comes from the inside out, and not the outside in. If you look up “core” in the online google dictionary, it will tell you that core: is “the central or most important part of something.” Our core is just that, our central most important part, concerning functional stability. Often when we read, talk or hear about a strong core, it comes with an image of a defined six-pack. This imagery is very misleading; a six-pack does not equal a strong functional core! The innermost part of our core is our breath/our diaphragm and is not externally visible. To address back pain through a comprehensive therapeutic approach it is essential to start here, with our breath.

The Diaphragms Role

For a long time, the diaphragm (“a dome-shaped, muscular partition separating the thorax from the abdomen”) [2] was thought only to be a muscle for breathing. However, a study performed by Professor Kolar and his colleagues revealed that the diaphragm serves two functions: respiration and stabilization.[3] A second study conducted by the same group demonstrated that the diaphragm's two functions can take place simultaneously: it can stabilize and participate in respiration at the same time. [4] These two studies supported Professor Kolars finding that individuals who are unable to contract the diaphragm for stabilization effectively are at higher risk for back pain. [5] The ability to effectively utilize your diaphragm for respiration and core stability simultaneously is essential in attaining and maintaining functional core stability, and alleviating/preventing back pain.

How we breathe, and how we utilize our diaphragm can stabilize and protect our spine and strengthen our core, or do the exact opposite. More often than not improper breath patterns, lead to instability in the spine, which eventually results in back pain, and tension in the neck and shoulders.

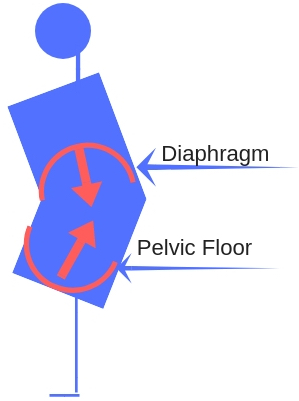

As I have stated above the diaphragm serves two significant roles: respiration and stabilization. However, it cannot complete stabilization on its own; it needs proper participation from the pelvic floor (“the muscular area in the lower part of the abdomen, attached to the pelvis”) [6] and the core wall. In healthy function, the diaphragm and the pelvic floor work in unison and are stacked parallel to each other. What I mean by stacked parallel is that they are aligned within the body. For example, if you imagine the abdomen as a soda can, the diaphragm is the top, and the pelvic floor is the bottom (See fig. 1). This parallel stacked position allows pressure to be built up within the abdominal cavity which stabilizes the spine and protects the low back

Fig. 1

On inspiration the diaphragm moves down, and presses out against the ribs, creating pressure within the abdominal cavity. This Intra-abdominal pressure (IAP) is contained through the pelvic floor and the abdominal wall maintaining their respective tension. If you press down on the top of your unopened soda can, it will stay stable because the sides and bottom are taut and active in response to the internal pressure from the carbonation (IAP).

However a common finding in people with low back pain is that the diaphragm and the pelvic floor are not stacked parallel to each other, they are either pointing away from each other towards the front (Fig 2) or towards the back of the body (Fig. 3). As a result, proper pressure and tension are not built up and maintained within the abdominal cavity; leaving the spine unstable, and the muscles of the low back and the walls of the core locked short or long. This instability represents in the body slumping forward in the shoulders and rounding through the low back or overarching in the opposite direction. Take our soda can analogy, if you put a dent in one side of your can, and then apply pressure to the top, the can will buckle. When this improper posturing represents in the body, the diaphragm is unable to move down and out, and unable to create IAP effectively, and the result is instability in the core. In response, the activity of breathing often moves up into the chest cavity resulting in the muscles of the neck and shoulders working to lift and expand the ribcage for respiration. Over time, taking 23000 breaths a day this way leads to chronic tension in the neck and shoulders muscles

Fig. 2

Fig.3

If you look at figure 1, where the diaphragm and pelvic floor are stacked parallel to each other, you will see that there is an equal length within the muscles of the front of the body and the back of the body. However in our model where there is buckling in the spine forward (fig.3 ), the front of the body is stretched long and the lower back locked short, and the reverse is seen (fig. 2) when the buckling in forwards. This results in the lengthened muscles becoming weak and the shortened muscles being overworked and chronically tight= weak core and a painful lower back.

So how can you work to realign, and repattern your breathing? Below is a series of exercises that are a great starting point. Repatterning your breath is extremely important, and vital for overall balance within your body. It can be a challenge at first and feel very strange. Every body is different; therefore the cues and modification each individual needs are different. If you are struggling, or unsure if you are making necessary progress and changes, please reach out to us, through our contact us page, to schedule a personal consultation, where we can work with you one on one in person or virtually.

Begin by lying on your back with your legs elevated and your knees at a 90 degree angle. This position insures that your diaphragm and pelvic floor are stacked parallel, and that the muscles of your core and back are properly balanced.

Inhale and expand 360 degrees into your back, front, and sides (think out not up). Use your hands as feedback to insure you are breathing laterally into your ribs, down into your pelvic floor, into your belly and your back.

Maintain a soft engagement within the muscles of your core at the top of your inhale, and throughout the exhale.

Exhale, returning your diaphragm to its elevated position, while maintaining a lengthened and stable spine.

Repeat

When you feel confident in your breath expansion and stabilization, add the load of your own legs, and work to maintain the expansion and stabilization. If at any point you are unable to breath 360 degrees, or are unable to feel your ribs, low belly or back moving while you breath, return to exercise one.

Start: Neutral spine, with diaphragm and pelvic floor parallel to each other

Inhale using diaphragmatic breathing technique practices in exercise 1: - create supple but stable outward pressure.

Continue 360 degrees outward expansion/engagement as you exhale.

Lift your calves off the chair/support, and work to maintain diaphragmatic breathing and intra-abdominal pressure as you are tasked with holding the weight of your own legs.

Repeat and rest when needed.

Building on the exercises from above. Practice the same techniques, but with the added demand of upright stabilization, maintenance of a neutral spine, and stacked diagram over pelvic floor.

Inhale using diaphragmatic breathing technique practices in exercise 1 and 2: - create supple but stable outward pressure.

Continue 360 degrees outward expansion/engagement as you exhale.

Repeat.

Sources

[1] Information, H. and Statistics, B. (2018). Back Pain Facts and Statistics. [online] Acatoday.org. Available at: https://www.acatoday.org/Patients/Health-Wellness-Information/Back-Pain-Facts-and-Statistics [Accessed 30 Oct. 2018].

[2] Encyclopedia Britannica. (2018). diaphragm | Definition, Function, & Location. [online] Available at: https://www.britannica.com/science/diaphragm-anatomy [Accessed 30 Oct. 2018].

[3] Kolar P, Neuwirth J, Sanda J, Suchanek V, Svata Z, Pivec M. Analysis of diaphragm movement during tidal breathing and during its activation while breath holding using MRI synchronized with spirometry. Physiol Res 58:383-392, 2009

[4] Kolar P, Sulc J, Kyncl M, Sanda J, Neuwirth J, Bokarius AV, Kriz J, Kobesova A. Stabilizing function of the diaphragm: dynamic MRI and synchronized spirometric assessment. J Applied Physiol Aug 2010

[5] Reinold, M. (2018). Core Stability From the Inside Out. [online] Mike Reinold. Available at: https://mikereinold.com/core-stability-from-the-inside-out/ [Accessed 28 Oct. 2018].

[6] Collinsdictionary.com. (2018). Pelvic floor definition and meaning | Collins English Dictionary. [online] Available at: https://www.collinsdictionary.com/dictionary/english/pelvic-floor [Accessed 30 Oct. 2018].